I’m by no means what you’d call a Gamer, but I was still pretty disappointed last month when Rockstar Games announced they were pushing Grand Theft Auto VI to next year. Freakin’ May 2026. Real crushed, but also, not surprised. Even non-gamers like me know Rockstar’s notorious track record of stringing us all along. Dropping a trailer out-of-the-blue, giving us a vague release window two years down the line, and then, when we’re almost…ALMOST there, they jerk it right out of sight and drop-kick it into another far-flung fiscal year.

I’ve been a big fan of the Grand Theft Auto games my entire adult life. When I played the third game back in 2001, I was blown away by the 3-D open world realism: you, the player, did whatever you wanted with your little guy, B-and-E-ing your way through Liberty City, Rockstar’s satirical mock-up of New York City and the stanky, mobbed-up New Jersey. For me, this unchecked freedom was a revelation of new wave storytelling. I was kind of creating my own story as I went. And as much as I loved that gritty, 70’s NYC sandbox, how cool was it the next year when Grand Theft Auto: Vice City gave me a full-scale playground of Miami in the 1980s. Now, this was something. The neon, the leisure suits, the DynaTAC phones. It’s never left me, and I’ve always wondered what it would be like going back to Vice City, with a bigger map that would realize not just Miami, but the whole of Florida in all its beauty and eco-diversity, and, for that matter, its full spectrum of socio-economy. The slick Sonny Crockets and the barefoot, gator-rasslin’ Florida Man living together. Now, a year from the day I’m posting this, this is what Grand Theft Auto 6 will give me. I can’t wait.

And, yeah, of course I know they’ll push it back again. Probably ‘til next Fall. But whatever. It’s not like we don’t have all those great things to hold us over ‘til then. The original Vice City, for instance. We can play that again. And we can watch old episodes of Miami Vice or pop in Scarface. Or the always-fun-for-a-rewatch doc about the real-life cartel boys that built Miami in the 1980’s, Cocaine Cowboys.

Oh, and of course, we have so much great writing that the sunshine state has given us. John Macdonald’s houseboat-dwelling private eye Travis McGee is the star of one series I’ve gotten into recently, a beach bum by day who hunts at night all the con artists, perverts, and n’eir-do-wells that a place like Florida, smacking of rich tourists with deep pockets and shallow brains, attracts. There’s also the books of Carl Hiaasen, the columns of funny Florida Man Dave Berry, and, if we’re real desperate, and Rockstar does push the damn game back to next Fall, there’s always Tom Wolfe’s mediocre Miami-set novel Back to Blood.

For me, though, nothing really quite quenches my taste for the swampy, buggy Gothicism of Florida more than Elmore Leonard’s crime novels he set there. Like Macdonald, a contemporary of Leonard’s who got to writing about Florida before he did, Leonard recognized that Florida is the perfect host for the full array of human character, where cops and crooks mingle at the beach, where the ornate stucco mansions are paid for by the Dirty done in the swamp. Starting with Gold Coast in 1980, he set many of the novels there that would come to define his career’s golden age, and this summer, while I’m sorely biding my time, waiting for the inevitable further delay of GTA VI, my plan is to go back through all of them — in no particular order.

First stop: Rum Punch, his 1992 novel that hits all the beats of dichotomy I want in an Elmore Leonard Florida crime caper: the dingy slums of Miami and the sun-soaked avenues of West Palm. The hurricane-battered, tarpaper dope houses and posh beachside condos, and all the underworld enterprise that connects them. The lawyers, guns, and money, to quote Warren Zevon.

Well, not so much lawyers, but a whole lotta people trying to avoid dealing with them.

It’s pretty accurate to say that the law is a nuisance to just about everyone in an Elmore Leonard novel, especially the cops. In Rum Punch, he gives us just about his most honest and likeable character on the “straight” side of the thin blue line, and even he can’t avoid the temptation to do dirty. He’s Max Cherry, an ex-cop from Chicago, now living in South Florida and coasting through middle-age as a bail bondsman who’s lost all interest. In Leonard’s world, most bail bondsman are greedy opportunists, but not Max. Not at first, anyway. He’s too tired to be corrupt, and so complacent to conflict that he keeps paying his long-estranged wife Renee a monthly allowance to run a pretentious art gallery in the mall just to avoid an argument.

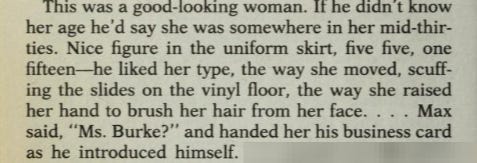

But all that changes when a new woman walks into his life, right past the guard gate of the Miami-Dade County stockade and reeking of jail. This is Jackie Burke, an aging flight attendant with a bottom-feeder airline flying cheap tourists to the Bahamas. She’s just been arrested coming off her most recent flight, a sandwich bag of cocaine in her purse she didn’t know about and fifty thousand dollars she did. For Max, his job has always been a clinical ordeal, a doctor-patient kind of interaction where the emotional stakes are fully counter-weighted by the offenders he bonds out. But when he sees Jackie, the scale flips quick the other way1:

Handing her his card being his natural impulse to resist her. You know, keep it professional.

But Max can’t help himself, offering to give her a lift home from jail, but not without going for a drink first. Pretty soon, Max is finding more excuses to see Jackie Burke. Clearly drawn to her quiet confidence — the way she handles herself, determined to slog through the muck of middle-age with cool grace. It rubs off on him, and pretty soon Max resolves to give up the bond business and break it off with Renee. To celebrate his newfound independence, he starts sleeping with Jackie.

Of course he knows none of this comes easy. For one, there’s Jackie’s trouble with the ATF, which he’ll need to help her deal with if he wants to run away with her. By process of elimination, Max figures it’s on account of firearms: the $50k in her beauty bag is coming from the sell of machine guns by Ordell Robbie, Jackie’s bail benefactor, who Max meets for the first time in the wood-paneled confines of his “Gentlemen Prefer Bonds” office. Taking ten thousand cash and no straight answers from him, Max knows Ordell’s type — “The kind of guy who worked at being cool, but was dying to tell you things about himself” (p. 18). Max could care less. But then, the fella he bonds out for Ordell turns up dead in the trunk of a stolen Olds right after he talks to the cops, and with Jackie’s recent proposition from ATF Agent Ray Nicolette to talk or go to jail, Max doesn’t need his old cop instincts to see a pattern of deed and execution with Ordell. Now, with Jackie copping a deal with the feds to lure Ordell into being caught red-handed with half-a-million dollars in gun money, Max sees his chance to save the woman he loves from her justice system love triangle.

None of this is to say that Max Cherry runs you through the pages of Rum Punch as he fights for Jackie and her freedom. Although, modest as Max is, he’d like to tell you it’s his story, just as Ordell, arrogant and braggadocios as he is, would have you believe it’s his. Nope. What neither of them know is that it’s Jackie’s show all the way. Hell, I’m not even sure Elmore Leonard knew while he was writing the novel how much Jackie’s running the game. Take, for example, a rare, quiet moment he gives us with Jackie, right before she’s poised to double-cross everyone for the half-million: Ordell, the cops, maybe even Max. There she stands in the food court of a mall where it’s about to go down, looking up at one of those live mannequins, asking her, “‘How long do you have to do this?’

This scene coming late in the novel, Jackie sees herself the way all the men do: disarmed, defenseless, keen to be exploited. Annoyed at the prospect, Jackie pushes past the woman: “You can do better than this.”

It reads like the moment when Leonard snaps-to also, like he knows he’s written a better, smarter character than a woman showing off shoes and a faux-leather travel bag.

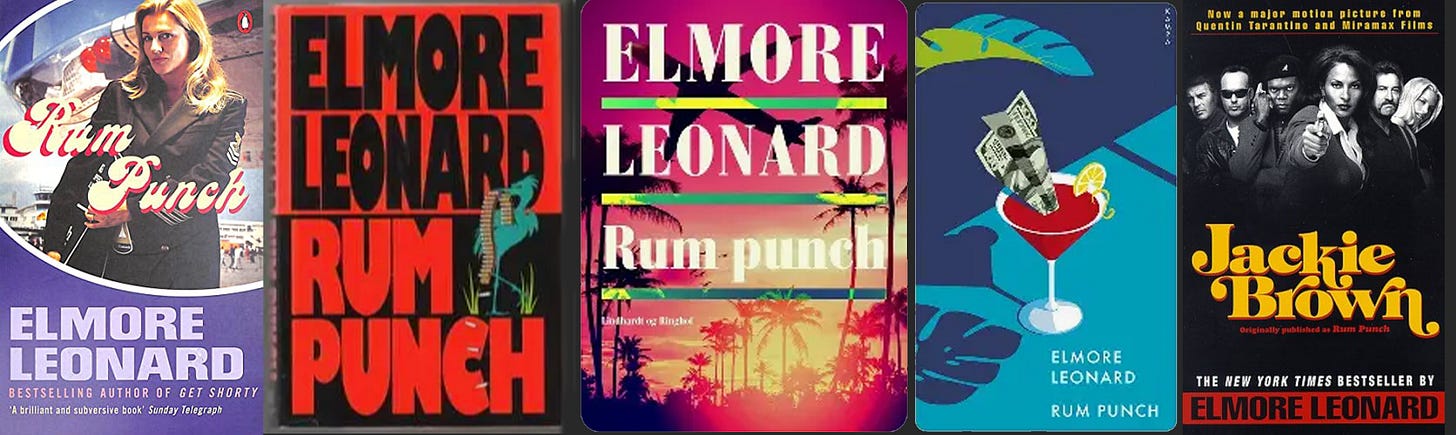

It’s easy now, more than 30 years after Rum Punch was published, to see Jackie Burke from the get-go as a keen, headstrong woman who’ll get her way. And, of course, much easier if you’ve seen Quintin Tarantino’s 1997 movie he based on the novel, where he changed her name to “Jackie Brown” and cast Pam Grier in the part, the posterchild of 70’s badass feminism. But still, Leonard does a lot to make Jackie an unassuming player whose playing everyone all along. Rarely, for instance, does he show things from Jackie’s perspective. For the most part, everything happens from the point-of-view of the men — Ordell, Max, and Agent Ray Nicolette. But little do they know that all they know is what she tells them about the plan and how she looks when she’s telling them. A two-time divorcee’ to total losers, she is a past master of downplaying her confidence game to pull the switch on conniving men. Even Max, though not as plotting, is too lovestruck to see the game she’s playing, how she’s using his feelings for her against him. Sure, he’s a smart guy, and he’s pretty sure she’s up to something that will ultimately leave him alone and heartsick, but whatever; at least he gets to watch her while she takes him for a ride.

⚠️Spoiler warning from here on out — skip on down to the bottom if you haven’t read Rum Punch or seen Jackie Brown.

Don’t be thinking from my summary here that Rum Punch was pretty much carbon copied by Tarantino into Jackie Brown, and that alone should excuse you from reading it. Or reading it again, as I’ve been thinking all these years.

Like a lotta folks who were jonesing Grand Theft Auto-style for Tarantino’s next project after Pulp Fiction in the 90’s, I read Rum Punch with rapt attention before I saw the movie. And, yeah, when I finally saw Jackie Brown, it was about as satisfying a page-to-screen adaptation as maybe you could get. To this day, I still think it’s my favorite Tarantino to watch (maybe not his best movie, but one I can put on whenever, just to pass the time and hang out). So, yeah, with so much love for the movie, I mostly always thought it was a waste of good reading time to go back to the book.

Man was I wrong.

Just like we watch Tarantino movies on repeat, it’s an absolute blast to go back through an Elmore Leonard book for the ways he tells you his stories. Rum Punch being no exception. Take, for instance, one part I always remembered from the book that’s done beat-for-beat in the movie: Aging con and Ordell-associate Louis Gara shooting down his nagging accomplice Melanie in the mall parking lot. In Jackie Brown, De Niro hands in one of his best parts playing Louis, and you really feel his stress — his accumulating regret at having wasted his life on small cons, and doing them with such ratty people like Ordell and Mel. What a minute of catharsis you see him have when he pulls out the gun you didn’t know he had and pops two into Bridget Fonda’s Melanie. It’s classic Tarantino — shocking and funny. But seeing how Elmore Leonard tells it makes it feel box-fresh all over again:

“Once she saw [the gun] she shut up. Her face went blank. But then, Christ, she started talking again. Louis didn’t hear what she said because right then he shot her. Bam. And saw her bounce off one of the cars. Bam. Shot her again to make sure and because it felt good.” (p. 294)

One of the best scenes in the movie, definitely heightened by the book. Good as De Niro is, and the whole cast for that matter, you get another level of knowing characters like Louis, how they think when they shoot someone.

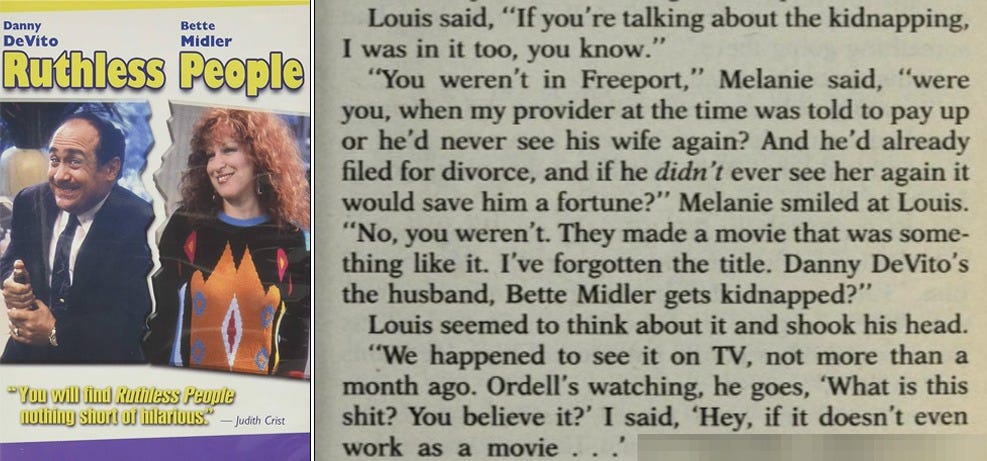

Speaking of Louis, you find out so much more about him in Rum Punch that you only get a hint of in Jackie Brown. For me, a major reason I wanted to go back to Rum Punch first in my foray back into Elmore Leonard’s Florida underworld is that I found out, in the years since first reading it in high school, that it’s actually his second book showing the exploits of Ordell and Louis. Showing you how they got their start together in Detroit. The Switch (1978) is less a straight-up thriller like Rum Punch. Really more of a farce, it’s all about a scheme they hatch to kidnap the wife of a rich country club-type, only to have things go bananas when it turns out he doesn’t want her back. I know, I know, it sounds exactly like the plot of the movie Ruthless People (1986), and clearly Elmore Leonard was miffed at how Hollywood ripped him off, and he includes a funny exchange in Rum Punch between Louis and Melanie (also introduced in The Switch) that brings all of that to light.2

But nevermind all that. The Switch is so worth reading because it adds a whole new level of drama to Louis and Ordell’s relationship, one that taints it with a lot of sadness and tragedy. Of course, you don’t need to read The Switch to know the full trajectory of their partnership, which ends in Rum Punch with Ordell shooting Louis on a dirty backstreet in South Beach after he majorly fucks up. But in The Switch, you see not just partners, but buddies, birthed and educated in the slums of post-war America, brought together by an indifferent justice system. They see each other. But in the intervening years between that novel and the events of Rum Punch, Louis goes back to jail, which this time, finally breaks him. Deflates him of all purpose and attitude. Something Ordell just can’t understand, or doesn’t want to believe is possible. “What’s wrong with you, Louis?” he says, leaning over the hole he just put in the chest of his old partner-in-crime. “Shit, you used to be a beautiful guy, you know it?”

And that’s Elmore Leonard at his absolute best. His books can be breezy, fun beach reading, and with Rum Punch, you get all that — a taut, smooth, and very funny-at-times caper. But also you get a gritty comment on what a life of crime does to people like Louis. Because one thing Leonard tells us that Tarantino didn’t in his movie is that Louis actually considers himself a “good guy” on the road to reform. Working for Max Cherry at the beginning of Rum Punch, placed there as a kind of spy for the crooked insurance company that owns his bond business, Louis appears to have put his past as a gentlemen bank robber, ripping off bank tellers with kindly, grammatically correct notes, behind him. But what Leonard notices about people like Louis that not a whole lot of genre writers of his time did is that prison has a way of turning good people into lifers of self-pity and desperation. How it also hooks them up with people like Ordell, society’s truly monstrous, who see in small-time guys like Louis proteges to mold, Svengali-like, into pawns to do their dark bidding.

So that’s about all I have to say on Rum Punch for now. Let me know what you thought about it (the book or my thoughts on it) in the comments below while I go onto the next one, which I’ll admit, I already have. Glitz (1985) is not about Miami, but a cop from Miami, who goes to Atlantic City after a psycho criminal he put away kills the hooker he fell in love with. So keep checking back here for when I review that!

If you liked this review and wanna support me in writing more, feel free to, ya know…

By the way, you can borrow the e-book of Rum Punch from the Open Library.

All quotes are lifted from the movie tie-in publication of the book, Dell 1997

Of course, The Switch eventually got its own movie adaptation years after people mostly forgot about Ruthless People. Check out Life of Crime (2013), starring Mos Def as Ordell, Isla Fisher as Melanie, and John Hawkes as Louis, who’s so good in the movie that I was actually imagining him, not De Niro, as I read through Rum Punch this time around.

I'm a Floridian, but I've never read any Elmore Leonard. I have enjoyed a few by Hiaasen.

I'm meaning to read some Hiassen this summer, too!